Greenaction supports Cahto & Wailaki tribal members and other Laytonville residents fighting for health, justice, and relocation away from toxic contamination.

The Cahto Tribe, tribal members, and other residents are rising up to defend their right to life.

Between 1950 and 1993, Mendocino County operated two landfills in Laytonville that were improperly managed and continue to contaminate surrounding wells, springs, groundwater, air, and soil. Eyewitnesses reported illegal dumping of toxic waste and open burning of waste materials. Cancer, miscarriages, and respiratory illnesses are only a few of the health concerns the community members have endured for decades but enough is enough.

The Cahto Tribe and other Laytonville residents are demanding action in hopes to ensure that everyone can enjoy a safe and healthy future. Their community demands include:

- Relocation of Rancheria residents who want to move to a new reservation on uncontaminated, traditional land

- Relocation of other nearby residents who want to get out of harm’s way

- Financial assistance to help with healthcare and moving costs

- Medical insurance and transportation to medical appointments

- Water filtration systems for those living on or near the Cahto Rancheria

We stand with Laytonville and will support them as they move forward with this battle! CLICK HERE to read more about the history of the Laytonville struggle!

READ about the Community Health Final Survey Results

READ about the Community Health Initial Survey Results

SEE photos and videos of the Laytonville Community

August 25, 2018

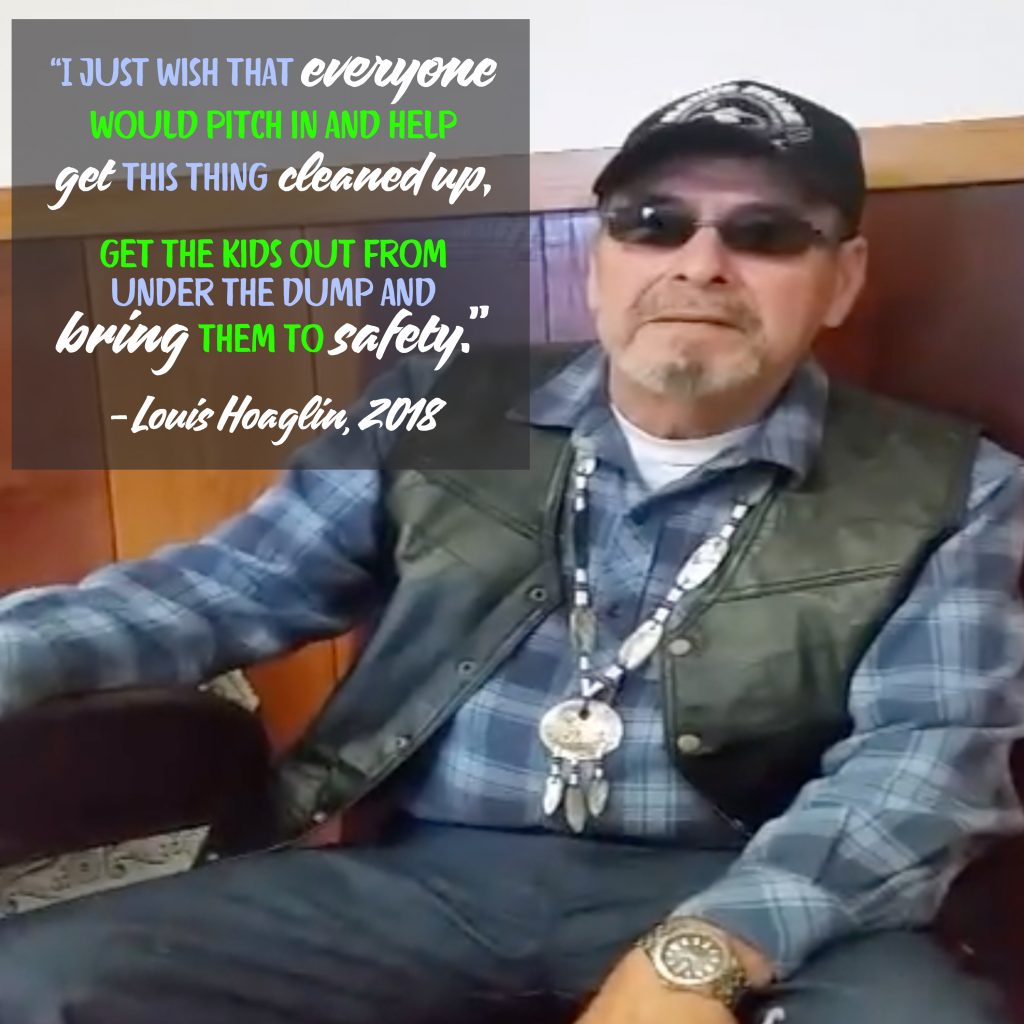

Laytonville, CA: R.I.P Louis Hoaglin, Chairman of the Wailaki Tribe

WATCH Video of Plea for Help from Wailaki Tribal Chairman

Laytonville preliminary results for a community health study show that people in Laytonville and Laytonville Rancheria are 3 to 4 times more likely to have cancer there than residents elsewhere in California Listen below:

Support our work today!

Laytonville Landfill Timeline 2022

Background and Timeline for Laytonville Landfills Between 1950 and 2022

There were two Solid Waste Disposal Sites operated by Mendocino County – one on the edge of the Cahto Tribe Rancheria and the other in a Laytonville residential area. The first site was opened in 1950 and closed in 1968 because of toxic contamination. The other site opened in 1968 and was closed in 1993 because of toxic contamination. Both sites were improperly capped and have continued from that time forward to contaminate surrounding wells, springs, groundwater, air, soil, and discharge leachate into Cahto Creek, Ten Mile Creek, and the South Fork of the Eel River.

Timeline of Key Events

1950 – The county leased the land for the first open burn dump (Solid Waste Disposal Site) located in the middle of a residential subdivision. On July 29, 1966, a letter was sent from Mendocino County Health Officer, C.R. Kroeger, MD, and Director of Sanitation, David C. Long, R.S. to Mendocino County Board of Supervisors. indicating the need to close the first Solid Waste Disposal Site because of unsanitary conditions and open a new dump.

1968 – The first Solid Waste Disposal Site was closed and a new Solid Waste Disposal Site opened above the Cahto Rancheria.

1974 – Clean up and abatement order #74-95. David Joseph from the North Coast Water Quality Control Board determined that “The County of Mendocino is negligently or intentionally causing or permitting the discharge of leachate….” And “The discharge of said waste is unreasonably affecting the water quality in that it is deleterious to fish and other aquatic life which exist in said waters to a degree which creates a hazard to the public health since downstream waters are used for domestic and agricultural water supply and will therefore create a condition of pollution which threatens to continue unless the discharge of waste is permanently abated.” And, “Permanently abate the threat of any further discharge of waste to the waters of Cahto Creek and its tributaries by November 1, 1974.”

In the 1975 Waste Discharge Requirements Order #75-50, David Joseph from the North Coast Water Quality Control Board emphasized that there are wells in the vicinity of the landfill.

Pg 1, par. 4 states that “…however, some wells are present in the vicinity.” The well that provided water to the Hoaglin residence was one of those initial wells that were later tested in 1993 and found to be contaminated. (See NET Pacific Testing Report)

David Joseph makes the erroneous claim “Pg 1, Par. 5: “Land within 1000 feet of disposal site is unimproved forest and range land.”

David Faulkner from Air Quality Control Board States in his letter dated March 10, 1993: “As the Laytonville landfill has many residences within 1000 feet of the perimeter and of the facility, it should have been classified in category I and testing should have been more thorough. Additionally, the ambient air testing was wholly inadequate for even a Category II facility.”

Pg 3, A. Discharge Specifications. 10. “There shall be no discharge of leachate or other liquid waste to any tributary of the Eel River.” Yet in a 1986 site visit response to the complaint. Thomas B. Dunbar, California Regional Water Quality Control Board concluded that “Waste Discharge Requirements Order No. 75-50 have been violated and threaten to continue to be violated.”

The Waste Discharge Requirements Order No. 75-50 was never followed properly and is not being followed today even after the Solid Waste Disposal Site has been closed since 1993. This site is still discharging leachate to the waters of Cahto Creek, a tributary of Ten Mile Creek, which is a tributary to the South Fork of the Eel River.

1987-88 – The first formal testing of the Solid Waste Disposal Site titled: “Air Quality Solid Waste Assessment Test Report for the Laytonville Waste Disposal Site” Pg 30 & 36 contain the results and location of extremely high concentrations of contamination.

1993 – Letter from David Faulkner, Air Pollution Control Manager from the Mendocino County Air Quality Management District indicating “inappropriate testing and a reference to the 1987 testing that showed high levels of ethylene dichloride, freons, and methylene chloride.

Solid Waste Disposal Site Closed after public outcry over documented contamination.

1998 – Solid Waste Disposal Site capped improperly and or improperly maintained. (Site visit: 2017 Sandy Karinen, Senior environmental scientist with the California Department of Toxic Substances Control)

2000 – Cahto Tribe requests assistance from the State of California culminating in Technical Outreach Services for Native American Communities (TOSNAC)

2002 – The Cahto Tribe received a modest EPA One Stop Grant to support the establishment of a Tribal EPA technology office. Grant objectives include the development of GIS/GPS data skills, data management, reporting, and exchange systems.

2005 – Cahto Tribe Health Survey. Taken improperly and completely inaccurate. A new health survey is in progress with early results demonstrating a high concentration of cancer clusters surrounding the Solid Waste Disposal Site area.

2016 – Multiple site visits from CalEPA and renewed effort to bring local, state, and federal agencies to deal with the effects of the landfills on the population of Laytonville.

2017 – BIA testing: The BIA has made several site visits and performed at least two controlled tests on the Cahto Rancheria this year.

2017 – CalRecycle and CalEPA have coordinated to do testing on the landfill nearest the Cahto Rancheria.

Spring 2018 – 273 Laytonville residents partake in an updated community health survey. READ the Community Health Final Survey Results.

2021 – CalEPA, at the request of Cahto Tribe, Greenaction, and California Environmental Justice Coalition, meets with the Cahto Tribe, but no progress is made to help get tribal members and other residents out of harm’s way

January 2022 – Cahto Tribe Community Health survey distributed to tribal members

2022 – The struggle for health injustice continues…